A growing industry aims to remove carbon from the atmosphere—but it’s still in its infancy, and greenhouse-gas emissions remain dangerously high.

Monte Markley, a geologist who lives on a farm near Wichita, Kansas, describes his job as “putting things underground and keeping them there.” As an environmental consultant, he specializes in disposing of industrial waste in subterranean rock formations. “All through my career, I’ve helped industries deal with the things that come out of the back side of a plant that nobody wants to talk about,” he told me. In early 2020, he got a call from Shaun Kinetic, a co-founder of a Bay Area company called Charm Industrial. Kinetic, who has experience building robots, satellites, and rockets, wanted to know how to dispose of a particularly troubling kind of waste: the excess carbon that contributes to global warming.

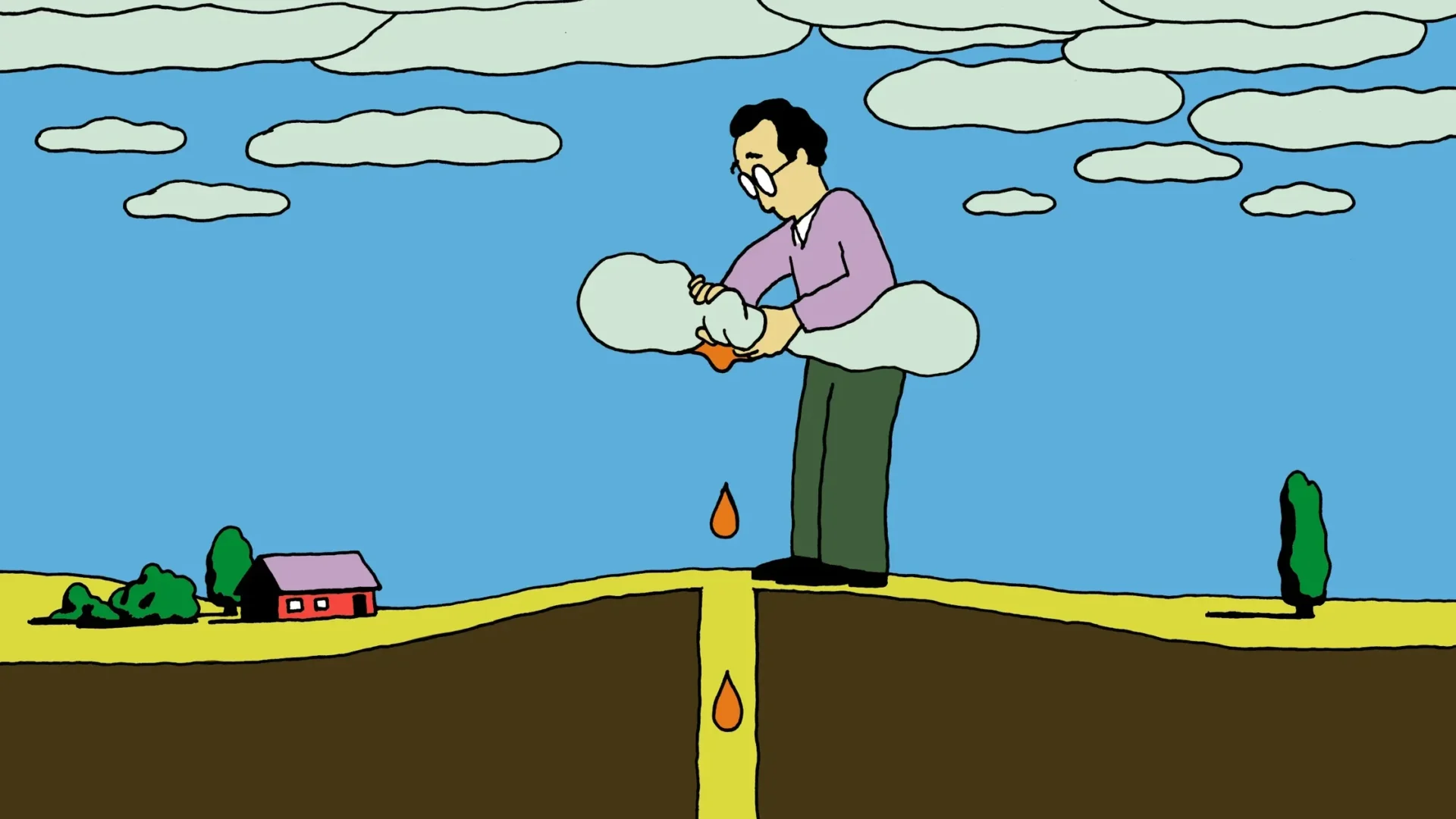

Markley had worked with companies that were trying to capture and store their own carbon emissions before they entered the atmosphere. But Charm was working with carbon that was already in circulation. The company was adapting a machine called a pyrolyzer, which heats plant material such as cornstalks in an oxygen-free environment, so that the plants turned into bio-oil, a carbon-rich liquid with the color and consistency of dark maple syrup. Kinetic wanted to know whether it was feasible to dispose of bio-oil underground. Markley said that it was—in fact, bio-oil would likely remain trapped there for centuries, if not longer. The process would resemble the drilling and burning of conventional oil, but in reverse.

In late 2021, Kinetic called again. Charm’s team hoped that, eventually, mobile pyrolyzers would allow the company to produce bio-oil on farms. To that end, Kinetic asked, could Charm Industrial test the latest version of its pyrolyzer on Markley’s land? Markley talked it over with his wife, Anna. Together, they had restored the acres they now farm, and both had a long-standing interest in conservation; the search for climate solutions appealed to them. Markley remembers thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool to be able to tell our kids what we were a part of?” The couple signed an agreement to lease land to the company.